Marxist architectural critic and theorist Manfredo Tafuri was, in my opinion, a cruelly unsung genius. His book Architecture and Utopia, as well as the inciting essay thereof, “Critique of Architectural Ideology” have been, personally, enormously formative, providing a stunning theoretical approach which serves to drag the self-consciously lofty stylistic perambulations and masturbatory preconceptions of architects and architecture down into the mire of the real world, situating the entire sordid discipline within the appropriate nexus of class struggle.

Anyway, as with most operaismo-aligned writers (other than Tronti and Negri), Tafuri’s work is only minimally available in english. Today, I’m going to try to rectify this a little bit by beginning a serialization of his essay on skyscrapers, “The Disenchanted Mountain”. The essay is a long and deeply researched meditation on a theme that obsessed Tafuri: the contradictory relationship between the architectural object, in which a tyrannical design position dominates under the heavy hand of the designer, and the riotous, untamable, unplannable environment of accumulated capital in which it is situated.

The essay is, as far as I can tell, not available online in english, but some years ago I purchased the essay collection The American City: From the Civil War to the New Deal, translated by Barbara Luigia La Penta and with three additional essays by Giorgio Ciucci, Francesco Dal Co, and Mario Manieri-Elia for access to the essay. I have now begun the process of making it available digitally, similarly to what I did for Irene Breugel’s critique of Harvey, but unlike that essay, which is much shorter, “Disenchanted Mountain” is over a hundred large-format pages and includes a ton of photos. So, I’ll be serializing it here, and publishing it as a pdf when I’m all done. Anyway, without further ado, here’s the first 10 pages or so of the essay.

The Disenchanted Mountain: The Skyscraper and the City

Manfredo Tafuri

Original citation:

Tafuri, M. (1979). The Disenchanted Mountain: The Skyscraper and the City. In B. Luigia La Penta (Trans.), The American City: From the Civil War to the New Deal (pp. 389–528). MIT Press.

Introduction

…Jimmy Herf came out of the Pulitzer Building. He stood beside a pile of pink newspapers on the curb, taking deep breaths, looking up the glistening shaft of the Woolworth. It was a sunny day, the sky was a robin's egg blue. He turned north and began to walk uptown. As he got away from it the Woolworth pulled out like a telescope. He walked north through the city of shiny windows, through the city of scrambled alphabets, through the city of gilt letter signs.

Spring rich in gluten…Chockful of golden richness, delight in every bite, the daddy of them all, spring rich in gluten. Nobody can buy better bread than PRINCE ALBERT. Wrought steel, monel, copper, nickel, wrought iron. All the world loves natural beauty. LOVE'S BARGAIN that suit at Gumpel's best value in town. Keep that schoolgirl complexion….JOE KISS, starting, lighting, ignition and generators.

This is the way John Dos Passos begins the chapter entitled “Skyscraper” in Manhattan Transfer, published in 1925. In the “city of scrambled alphabets” and kitsch publicity – “All the world loves natural beauty” – Cass Gilbert's Woolworth Building is seen as a magical event. In the literary context, its telescopic mass provides an interceding image between the absolute unnaturalness of the "city of gilt letter signs" and the disenchanted nostalgia for a “spring rich in gluten”.

Thus the skyscraper is perceived as an element of mediation, a structure that does not wholly identify with the reasons for its own existence, an entity that remains aloof from the city. The Neogothic structure of the Woolworth Building soaring upward in successive stages before the broad, open space of City Hall Park was an explicit response to the skyscraper as developed by the Chicago school. In Chicago an attempt had been made to achieve visual and dimensional control of the skyscraper, an organism that, by its very nature, defies all rules of proportion; in New York, the ascending lines of force of this organism of potentially infinite development, were given free reign; the isolation of the Woolworth Building is in perfect accord with this concept.

This was an old controversy, however, and Cass Gilbert's work, far from initiating it, actually concluded it. At the end of World War I, the experiments and acclaimed models of George B. Post, Harvey Ellis, Louis Sullivan, Daniel H. Burnham, and Gilbert no longer held up in face of the increasingly explosive problems of the urban structure they conditioned. The skyscraper as an “event”, as an “anarchic individual” that, by projecting its image into the commercial center of the city, creates an unstable equilibrium between the independence of the single corporation and the organization of collective capital, no longer appeared to be a completely suitable structure. The control of this “anarchic individual”, in the absence of the necessary institutional means, became an obsessive problem. In the early 1920s, the Woolworth Building, which captured Dos Passos’ imagination, could still serve as a model, but the reasons justifying its creation belonged to a bygone epoch.

The Chicago Tribune Competition

In 1922, when, with great fanfare, the management of the Chicago Tribune opened the famous competition for a new administration building for “the world’s largest daily newspaper”, the crisis of the skyscraper became strikingly evident. Significantly, the official program of instructions distributed to the entrants was wholly concerned with formal eloquence, while structural aspects were completely ignored. Thus beginning this examination of the business centers of the American cities with an analysis of the Chicago Tribune competition has a deliberate provocative intent. Moreover, since this argument must necessarily be presented in terms of key events, the competition of 1922 makes it possible to examine not only the unresolved crisis already mentioned, but also the relations between European and American architectural culture.

The history of the American skyscraper, from the first empiric application of the elevator to tall commercial edifices – such as the Jayne Granite Building in Philadelphia (1849-52), designed by William L. Johnston or the Equitable Life Insurance Company Building in New York (1868-70), designed by Gilman, Kendall and Post – to the types established around 1890 by George B. Post or Bruce Price, is, in fact, the history of a close relationship among technological innovations, structural innovations, and innovations in the design of the architectonic organism. Despite their disagreements, both Winston Weisman and J. Carson Webster make clear the thoroughly structural nature of the process of development of the skyscraper up to the impasse of the 1920s.1

This impasse was manifest by a break with the interrelationship of the creative factors that had previously characterized the development of the skyscraper. Between about 1900 and 1920, the tried models by now became canonical and the repertory fixed, construction in the large commercial centers left a series of problems unresolved. What had been, between 1850 and 1890, a continual development rich in results now became a process of involution.

In the first place, the intimate relationship that had existed between technological innovation and developments in the architectonic organism was sundered. By this time the rigid organization of the building industry and its division in infinite numbers of small firms contradicted the very nature of the skyscraper and gave rise to evasions and hybrid concessions to the ideology of the “Cathedrals of Business” on the part of the designers. In other words, architects resorted to a formal language that could adequately publicize and exalt the concentration of capital the skyscraper expressed, but they ignored the scientific study of its economic efficiency or technological possibilities.

Second, the single building operations within the city, as speculative ventures, entered into conflict with the growing need for control over the urban center as a structurally functional whole. In the face of the problem of ensuring the efficiency of the central business district in terms of integrated functions, the exaltation of the “individuality” of the skyscraper in downtown Manhattan, already dramatically congested, was an anachronism. The corporations, still incapable of conceiving the city as a comprehensive service of development, in spite of their power, were also incapable of organizing the physical structures of the business center as a single coordinated entity.

The triumph of eclecticism was the consequence of these unresolved problems, the expression of their passive acceptance. The completely uninhibited and pragmatic character of American eclecticism, however, actually had its origins in a tradition inaugurated with the Virginia Capitol, for which, in 1786, with Clérisseau’s help, Jefferson adopted the model of the Maison Carrée of Nîmes. Jefferson's intention was clear; the building had first and foremost to convey a composite significance – the sacredness of the lay temple, with its references to the Roman Republican virtues. Thus the capitol was a “ready made” in need of only a few functional adaptations. In this case, the values and meanings underlying its forms were accepted as a system of conventions; as such, they were interpreted as something stable and immutable.2

For Post, Corbett, or Cass Gilbert, just as for Jefferson and Latrobe, the European models had the character of a convention. The value they expressed changed – Republican virtues for Jefferson, the austere elementariness of Greek democracy for Latrobe, Gothic sacredness for Gilbert's “Cathedrals of Commerce”, which exalted business enterprise – but the architects’ indifference to the stylistic material remained identical. In the skyscrapers of the 1910s it is as if the architectural process were quite explicitly split in two; the effort at formal design was reduced to a minimum in order to allow maximal concentration on function and structure. Cass Gilbert's Woolworth Building (1911-13) is an illuminating example of this phenomenon.3

This primacy of structure and subordination of style was perfectly understood by Montgomery Schuyler in his famous article on the evolution of the skyscraper published in Scribner’s Magazine in 1909.4 Schuyler investigated the same subject further in 1913, in an article in which he discussed the Woolworth Building, Ernest Flagg's Singer Building (1906-08), and the Metropolitan Tower of Napoleon Le Brun and Sons (1905-09), leaving aside almost all consideration of their formal aspects.5 This critical practice was the result of a lucid distinction. On the one hand, there were the products of construction, such as skyscrapers, destined to a “distracted use” within the dynamics of the metropolis and valid for their contribution to the formation of the complex structure of the business centers; on the other, the architectural objects, such as Richardson's buildings, which Schuyler analyzed with minute attention-to their stylistic expression-in other words, works separate from the “working city” in which style could gain full autonomy.6

What is of interest here is that this particular line of criticism persisted in America up to the early 1920s. In 1921, in an article illustrated by Hugh Ferriss, C. Matlack Price stated explicitly that “to be able to see a building without seeing its stylistic rendering is to see architecture”.7 Praising the Woolworth Building and Helmle and Corbett's Bush Building, Price continued, “From the point of design, the Gothic manner affords a peculiarly happy solution for the problem of terminating the tall building, as is admirably evidenced in the top of the Bush Building. This is probably one of the finest silhouettes of all the tall buildings of New York”.8

This is exactly the opposite of the formalist point of view. Asserting the primacy of the organism over formal expression, Schuyler and Price assigned a secondary, instrumental value to architectural style, an attitude directly antithetical to the ideological value attributed to the new, nonfigurative language by the European avant-garde in these same years. In a certain sense, a continual de-idealization of architecture was taking place in the United States. By emphasizing the purely conventional character of the use of “styles”, American

eclecticism of 1910-20 liquidated the organic conception of architecture; thus it fell into line with the concepts of organic architecture's bitter rival, the City Beautiful.

It was just when this process had reached its zenith that the crisis of the skyscraper and its consequent urban significance were made evident by the Chicago Tribune competition. Led by Robert McCormick, director of the great Chicago newspaper, the competition for the new building was actually part of a program to develop the northern area of the city, beyond the Chicago River, which had been an objective ever since the early years of the century.9 Significantly, however, despite this urban dimension of the Chicago Tribune’s initiative, the program of the competition insisted on the aim of creating “the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world” and exempted the entrants not only from any consideration of the relationship between the new edifice and the urban system but even from any adequate technological controls. The skyscraper of the world's largest newspaper, an organization intimately connected with the tumultuous development of the city of Chicago, had to be “an inspiration to [its own] workers as well as a model for generations of newspaper publishers”.10

The theme of “civic beauty” served to make attractive a speculative venture of vast proportions. In 1902, the Chicago Tribune had constructed its own 8-story building between Madison and Dearborn streets; after seventeen years, however, the congestion of the old business district and the newspaper's organizational needs advised a move to an area outside the Loop. The development of North Michigan Avenue, which had also received a strong impulse from Burnham’s plan, clearly indicated the best direction for the first decentralization initiatives. McCormick himself recognized this to be the most favorable area for a program aimed at overcoming the anarchic proliferation of building projects by coordinating the efforts of single proprietors with those of the municipal administration.11 In 1919, immediately after the completion of the artery, McCormick purchased the property at 431-439 North Michigan Avenue; by 1920 the bare functional block of the new Tribune Plant by Jarvis Hunt had already been constructed on the lot. The new skyscraper would therefore be situated between the Tribune Plant and the boulevard. The site of the Tribune’s future administration building was certainly in an enviable location. Situated as a crucial nodal point of Michigan Avenue, the site offered the possibility of constructing an edifice that would become a point of reference of urban scale and thus also accentuate the Chicago Tribune’s pioneering effort in the development of an area destined to become the necessary complement to the Loop.12

In spite of all this forethought, the organization of the competition seems to have been completely improvised. Ten American architects, among them Benjamin Wistar Morris, Bertram G. Goodhue, Howells and Hood, and Holabird and Roche, were expressly invited to participate, with expenses to be reimbursed fixed at $2,000. The original closing date was November 1, 1922, later extended by a month. The program for the competition, prepared by Howard L. Cheney, the Tribune’s advisory architect, was exceedingly general. The entrants had to present only two plans (a ground plan and a typical floor plan), plus elevations and one perspective drawing of their projects. The only functional consideration stipulated was that the designers should consider that, of the projected 400-foot building, only the lower floors were to be occupied by the Chicago Tribune; the upper floors would be leased to commercial firms. As already noted, nothing was requested in terms of technological considerations; indeed pure scenography was encouraged. The competition and its program met with enthusiasm among American architects, especially those invited to participate. And the jury, which was scarcely representative of the current trends in American architecture, was quick to arrive at a decision.13

The verdict was announced on December 3, 1922: the first prize of $50,000 went to Howells and Hood· the second of $20 000 to Eliel Saarinen; and the third, of $10,000, to Holabird and Roche.14 The publicity campaign did not end with the closing of the competition, however. Instead, it became an occasion for sensitizing the American public to the problems of architecture. Since June 1922 the Sunday Tribune had been publishing articles dedicated to the architecture of all periods and this continued through January 1923. At the closing of the competition, 155 of the 263 perspective drawings submitted in the competition were sent to twenty-seven American cities in an exhibit organized and financed by the Chicago Tribune.15

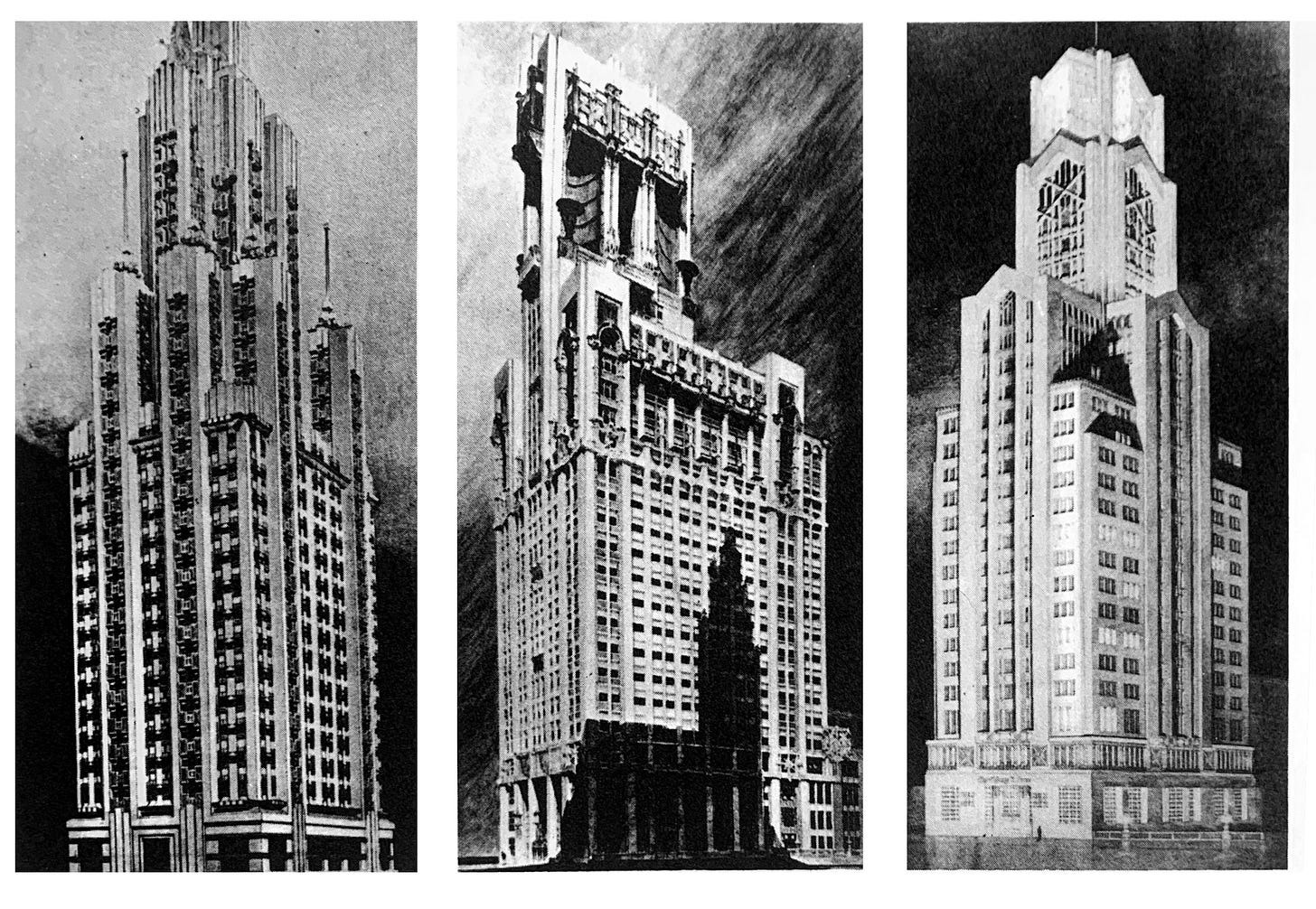

The massive participation by American architects – 145 entries – affords a comprehensive view of the architectural situation in the United States in the 1920s. The entire range of eclectic propositions appeared in a competition pervaded by the most absolute cynicism. The more or less literal Gothicism of Helmle and Corbett, of Paul Hermann, or of the design by Louis Bourgeois, Francis Dunlap and Charles L. Morgan was equivalent to the vacuous classicism of Benjamin Wistar Morris or Frank Fort, while Alfred Fellheimer and Steward Wagner's effort, or Paul Gerhardt's, to create “significant forms” led to pyramidally developed designs and the use of Egyptian imagery.16 The irony of the anthropomorphic designs presented by some cartoonists was thus not unjustified. The assortment of projects all too obviously bent on achieving some impossible qualitative distinction reflected the crisis of the skyscraper itself.

Among the American entries, however, were three projects that represented, each in its own way, the ultimate response of the Chicago School to the problem of the skyscraper – the designs submitted by Walter Burley Griffin, William E. Drummond, and Lippincott and Billson. In other words, by two former collaborators of Frank Lloyd Wright and by an architect closely linked to the same line of descent (Roy Lippincott was Griffin's brother-in-law and collaborated in Griffin's Australian projects).

Griffin’s proposal, prepared in his Melbourne studio during a period of professional crisis and stasis, was the architect’s last attempt to reassert himself in the American scene.17 The design pursues certain tendencies of his Australian work, including his experiments in the use of materials, which he carried out very successfully in his complex at Castelcrag, begun in 1921. But it also continues the expressionistic overwroughtness, based on the fracturing or multi- plication of forms and on a new eclecticism that he had adopted in the Chinese Club (1915) and Newman College (1916) in Melbourne and was to use again in the Melbourne Capitol Theater (1924) and the City Council Incinerator at Sidney (1934-35), as well as in his work in India. Griffin's skyscraper for the Chicago competition fits perfectly into this line of development. The monumentality of the lower block and the insistent display of the supporting structures of the stepped towers contrasts with the fractured treatment of the crowns of the towers and the window elements inserted like precious independent

objects. In this design Griffin, indeed, appears obsessed by purely graphic definition, as if he wished with this ostentatious multiplication to contest the very unity of the skyscraper.18 It would seem that in his Chicago Tribune project and the work of his last years Griffin was expressing a personal stylistic crisis; such self-criticism, however, was foreign to the current concerns of urban America. Although Griffin's design was undoubtedly poorly understood by the jury, an interpretation of the skyscraper as an exceptional object in which to inscribe autobiographical notations was also quite outside the scope of the competition. Lippincott and Billson's proposal, which attempts to endow a conventional organism with qualitative distinction by means of a geometric play in the vaguely Gothic-inspired terminal structures, managed to win an honorable mention.

Drummond's project, in contrast, is something of a shock and should perhaps be considered as the expression of an ironic attitude rather than a serious proposal.19 Grafted onto a uniform block of fifteen stories, which, according to the canons of the Chicago school, frankly reveals its structure, are two independent volumes with a jumble of decorative elements that reach an absurd rhetorical climax in the terminal tower. In a display of classical imagery worthy of the set of some early film spectacular in the style of Pastrone or Griffith, sort of enormous baldaquin composed of porticoes and exedras rises amidst gigantic tripods. At this point Drummond's polemical attitude toward the rhetoric solicited by the competition's sponsor becomes explicit. The architect's irony, however, is also a cover for his complete abdication. What is surprising in the attitudes of Griffin and Drummond is that both ignore completely Wright's hypotheses on the tall building – the cohesion of the Steinway Hall group had been sundered for some time.

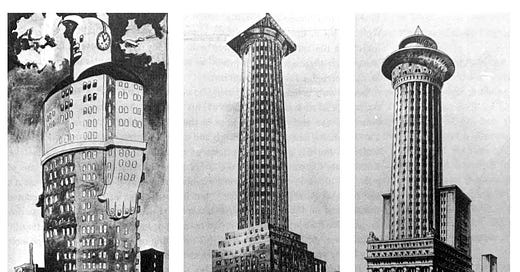

From left to right: Design by Holabird and Roche for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922 (third prize); design by Alfred Fellheimer and Steward Wagner for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922 (honorable mention); design by Frank Herding and W.W. Boyd, Jr. for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922.

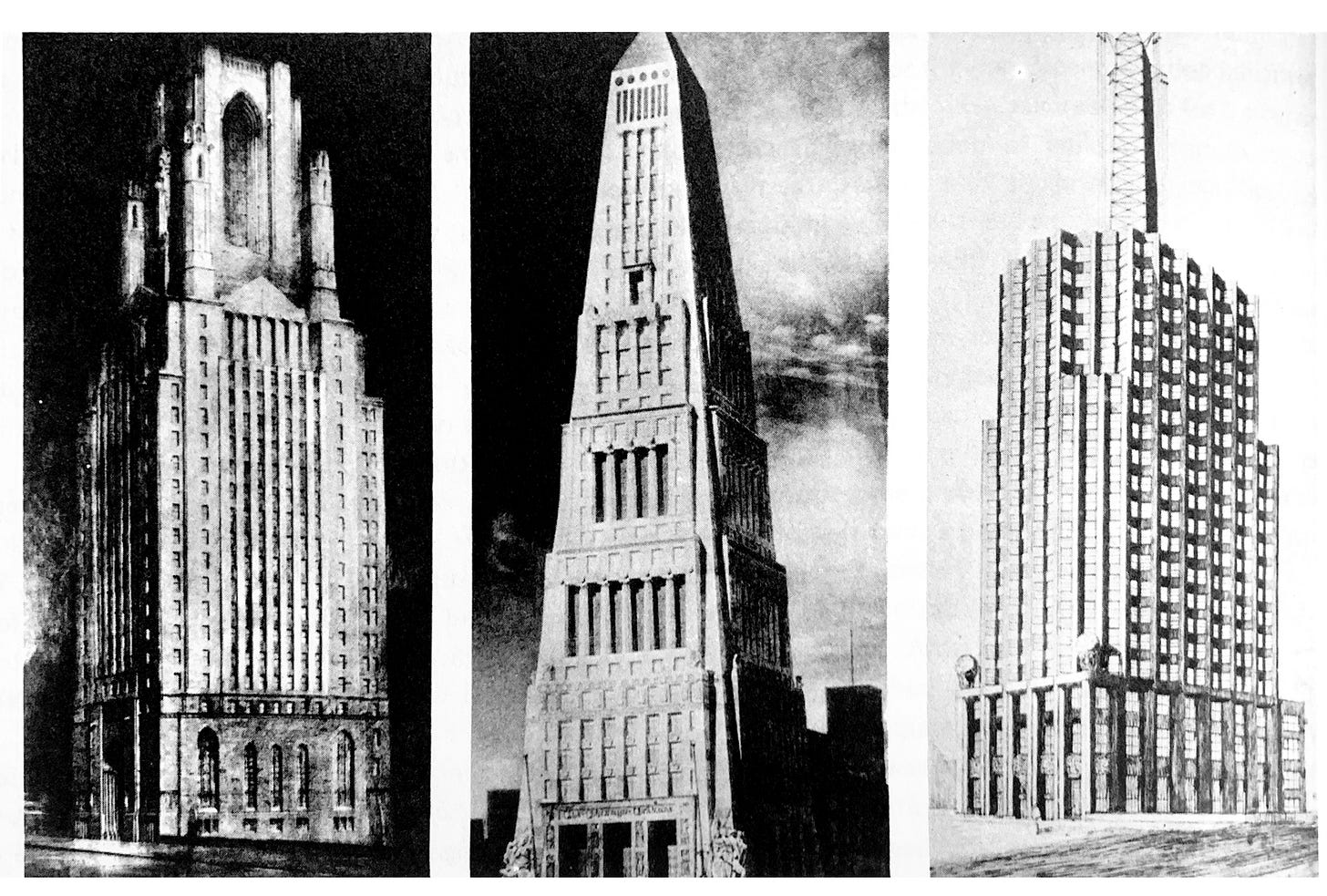

From left to right: Design by Walter Burley Griffin for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922; design by William E. Drummond for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922 (honorable mention); design by Lippincott and Billson for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922 (honorable mention).

The overall dreariness of the American participation in the Tribune competition stemmed directly from the absence of any consideration of the urban role of the skyscraper, such as that attributed to it later by Le Corbusier.20 The American architects no longer produced “events” on the metropolitan scale but, instead, labored to give formal stability to architectural objects the intrinsic laws of which were ignored. The iron-clad laws dominating the architectural profession and the construction market prohibited the necessary jump in scale from the individual object to the control of a complex structure like the commercial centers. This problem was confronted only in the limited terms of zoning proposals, and the pragmatic outlook reigning within the profession inhibited even the most advanced architects from proposing projects that called for anything more than restructuring the traffic system.

The absurdity of the Chicago Tribune competition lay in the desire to give stability to the concept of the skyscraper as an “object” by conferring upon it institutional sanctity, in other words, in the wish to exalt and consecrate the very autonomy that would now of necessity have been contested, if the goal had been, instead, to open up new perspectives. By imposing a symbolic mask that could result only in hybrid solutions, the 1922 competition can be seen, historically, to have marked a turning point in the conception of the skyscraper, at least on a theoretical level.

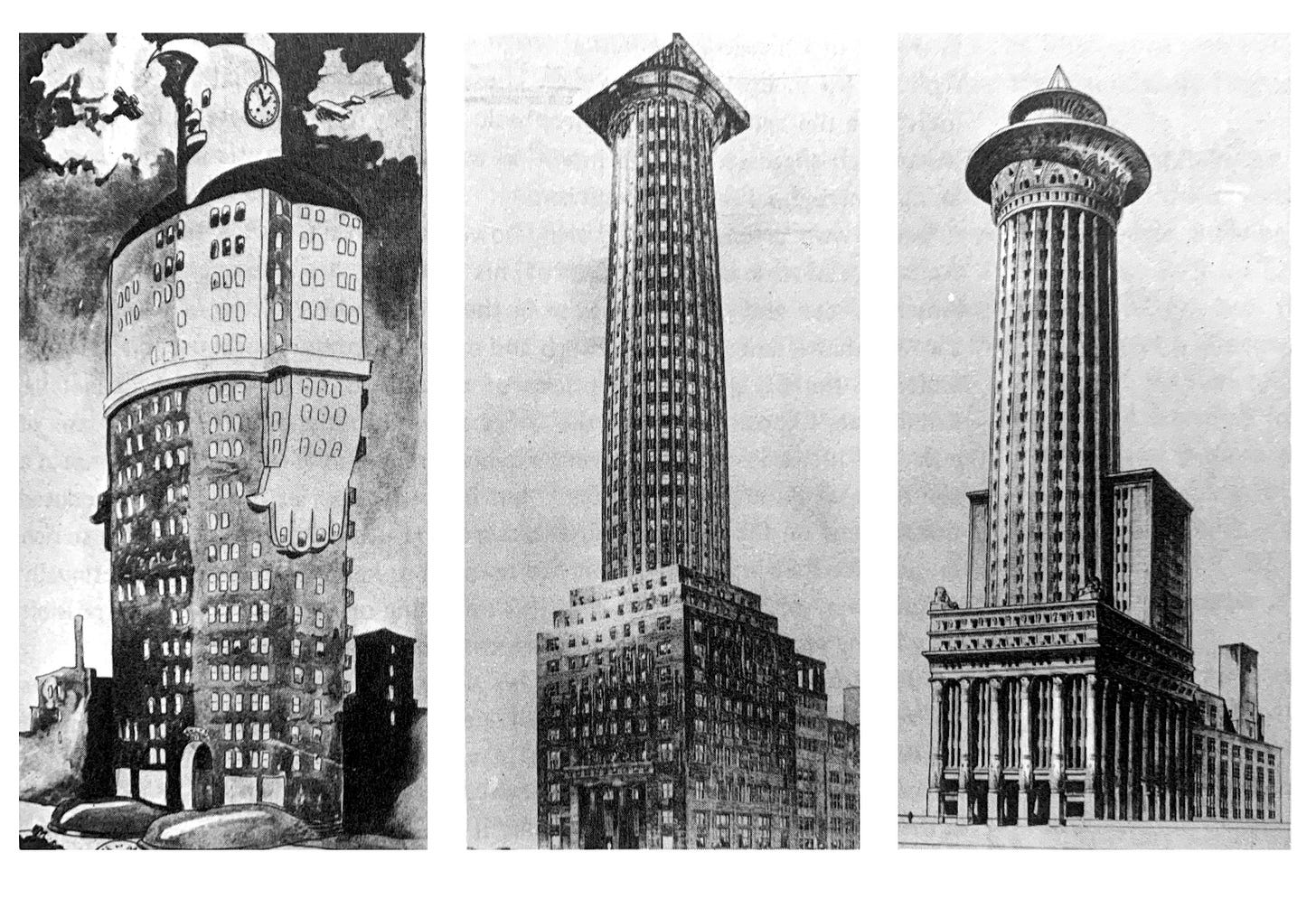

Satirical design by the Chicago Tribune cartoonist Frank King for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922; design by Adolf Loos for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922; design by Paul Gerhardt for the Chicago Tribune competition, 1922.

Only one of the symbolic themes treated in the competition is noteworthy: the skyscraper in the form of a column. Commentators on Adolf Loos's famous design in the form of a Doric column have often failed to note, in addition to the Austrian architect's exploit, two other proposals, by American architects, that adopt an analogous theme. In Matthew L. Freeman’s design, a stumpy Doric column rises above a block that terminates in triangular pediments; Paul Gerhardt of Chicago presented a design close to Loos’s, except that the Doric is replaced by an Egyptian column.21 These proposals would later be described as indicating the appearance of a prophetic pop spirit; in the case of Loos, at least, it has been suggested that his intention was ironic, his gigantic inhabited column being a mere mockery of eclecticism.

Loos’s own article on his design, however, contains not a trace of irony.22 Actually, all the contradictions of his position are present in his column. America, as seen and praised by Loos in the 1890s, was a nation of two faces; one showed that it knew how to absorb and make a supratemporal use, on a gigantic scale, of the European conceptions of order and form – the America of the Columbian Exposition – while the other uninhibitedly adhered to the laws of everyday life. Loos was to demonstrate his admiration for Sullivan’s attempt at a synthesis of these two opposites,23 but his own theories pointedly reproduced this schism: on the one hand, architecture, the utensil of a middle class so rich in qualities that in its daily life it had no need to keep its own values continually before its eyes; on the other, art, the “reflecting on values”, which was possible only in the pauses the universe of work concedes to contemplation.24

The Loos of years preceding the finis Austriae was not the Loos of the years following the war. In 1922, in full view of the Chicago Loop, he wished deliberately to “reflect on values”; in an obsessive search for nonephemeral forms, he wished to compromise the very symbol of order – and in its most authentically classical version – by using it in an everyday manner. The estrangement of the column became an allegory of urban estrangement. In his article, Loos explicitly referred to the formal alienation of the Metropolitan Building and the Woolworth Building.25 At the same time he spoke of the sensational effect created by the contrast between the cubic block and the fluted shaft of the column of polished black granite as the only one possible for spectators of an epoch “disillusioned like our own”.26

It would be possible to comment at great length on this Loosian ambiguity and play of equilibrium between the call to a supratemporal continuity of value and the gigantic enlargement of a fragment as a way of imposing its presence on the distracted metropolitan public. In fact, Loos seems in 1922 to have lost the clarity that characterized his prewar conceptions. His column is not symbolic; it is only a polemical declaration against the metropolis seen as the universe of change. A single column extracted from the context of its order is not, strictly speaking, an allegory; rather, it is a phantasm. As the paradoxical specter of an order outside of time, Loos’ column is gigantically enlarged in a final effort to communicate an appeal to the perennial endurance of values. Like the giants of Kandinsky’s Der gelbe Klang, however, Loos’s gigantic phantasm succeeds in signifying nothing more than its own pathetic will to exist – pathetic, because it is declared in the face of the metropolis, in the face of the universe of change where values are eclipsed, the “aura” falls away, and the column and the desire to communicate absolutes become tragically outdated and unreal. The mute silence of Loos’ column was the result of a utopian interpretation of the “new order” of industrial civilization, made by an intellectual who was constant in his attempt to find an ideal synthesis within the dramatically fragmented reality in which he lived.

But what was the model for this column? Was it not, perhaps, that tripartite form adopted habitually, from about 1880 on, in the skyscrapers of Post, Sullivan, and Holabird and Roche? Post’s Havermeyer Building in New York (1891-92), Adler and Sullivan’s Union Trust Building in Saint Louis (1892-93), Holabird and Roche’s Marquette Building (1893-94), and the Broadway-Chambers Building by Cass Gilbert (1899-1900) all seek a dimensional control of the “object” skyscraper according to a three-part division of basement level (base), principal homogenous structure (shaft), and crowning (capital). Such a transposition resolved the need to domesticate and possess completely the compositional elements derived from Beaux-Arts teachings in the terms of American pragmatism.27 The program implicitly assumed in order to arrive at such a solution was made explicit in Loos’ project of 1922, just how consciously we do not know, but so emphatically that no further comment on the theme was possible.

Although the two American architects were certainly far from Laos's intellectualism, the proposals submitted by Freeman and Gerhardt may also be explained in light of these considerations. Both endowed the skyscraper with a very particular expression, extraneous to the Loop and ostentatiously monumental. Their intent was obviously to create an allusion to the desire for stability of forms and institutions, a pause in the continuity of the “metropolis without quality”. It was Loos himself who had recognized in 1910 that such a pause can be identified only with the superfluous or with death.

See especially Winston Weisman, “New York and the Problem of the First Skyscraper”, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 12, no. 1, 1953, pp. 13-21; idem, “A New View of Skyscraper History” in Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., ed., The Rise of an American Architecture (Pall Mall Press, London-New York, 1970 , pp. 115-160; J. Carson Webster, “The Skyscraper: Logical and Historical Considerations, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 18, no. 4, 1959, pp. 126-139. This is not the place to take up the controversy between Weisman and Webster, which primarily concerns the criteria for classifying building types and the bases of comparison. It is interesting, however, to note that both authors' analyses are based on a structural criterion. It is not possible to give a complete bibliography on the history of the skyscraper here; among the significant contributions in addition to the works cited above, are Claude Bragdon, “The Skyscraper”, Architectural Record 21, Dec. 1909, pp. 84-96; Francisco Mujica, History of the Skyscraper, (Archeology and Architecture Press, New York, 1930); Carl W. Condit, The Chicago School of Architecture (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1964). The following articles by Montgomery Schuyler are indispensable: “The Skyscraper Up-to-Date”, Architectural Record 8, Jan.-Mar. 1899, pp. 230-257; “The Skyscraper Problem”, Scribner’s Magazine 34 Aug. 1903, pp. 253-256; “The Evolution of the Skyscraper”, ibid. 46, Sept. 1909, pp. 257-271; these articles are now available in William H. Jordy and Ralph Coe, eds., American Architecture and Other Writings by Montgomery Schuyler (Atheneum, New York, 1964). See also L'architecture d'aujourd'hui, no. 178, 1975; Archithese, nos. 17, 18, 20, 1976, all special issues devoted to this subject. On the relation between the development of the skyscraper and economic cycles, see Heinz Ronner, “Skyscraper: apropos Oekonomie”, Archithese, no. 18, 1976, pp. 44-49 and 55. The special issue of Casabella, no. 418, 1976, dedicated to the “Triumph and Failure of the Skyscraper”, is very general in its treatment of the topic.

See Fiske Kimball, Thomas Jefferson Architect (1916; reprint ed. with introduction by Fr. Doveton Nichols, Da Capo Press, New York, 1968); Thomas W. Waterman, “Thomas Jefferson. His Early Works in Architecture”, Gazette des Beaux Arts 24, no. 918, 1943, pp. 89-106; idem, “French Influence on Early American Architecture”, ibid. 38, no. 942, 1945, pp. 87-112; James S. Ackerman, "II presidente Jefferson e ii palladianesimo americano," Bolletino del Centro Studi A. Palladio 6, Pt. 2, 1964, pp. 39-48. See also Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia. Design and Capitalist Development (MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1976), pp. 25-34; this is a translation of Progetto e Utopia (Laterza, Bari, 1973).

See Montgomery Schuyler, The Woolworth Building (New York 1913), reprinted in Jordy and Coe, American Architecture; idem, “The Towers of Manhattan and Notes on the Woolworth Building”, Architectural Record 33, Feb. 1913, pp. 99-122. See also Gunvald Aus, “Engineering Design of the Woolworth Building”, American Architect 103, no. 1944, 1913, pp. 157-170; Edwin A. Cochran, The Cathedral of Commerce (Broadway Park Place Co., New York, 1916). The disastrous effects of the Woolworth Building on traffic congestion in Manhattan were brought out in a lucid article by Raymond Unwin, “Higher Building in Relation to Town Planning”, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects 31, no. 5, 1924, pp. 125-140. On the story of the inauguration of the Woolworth Building and the controversy the building provoked, see Rosemarie Bletter, “King Kong en Arcadie. Le gratte-ciel américain apprivoisé”, Archithese, no. 20, 1976, especially pp. 28-30.

Schuyler, “Evolution of the Skyscraper”. 5

Schuyler, “Towers of Manhattan”.

See the Schuyler articles collected in the chapter “The Richardsonian Interlude”, in Jordy and Coe, American Architecture, pp. 81-17 4.

C. Matlack Price, “The Trend of Architectural Thought in America”, Century Magazine 102, no. 5, 1921, p. 710.

Ibid., p. 712. American literature of the 1920s on the skyscraper, however, oscillated between deploring the effects of congestion provoked by tall buildings and interpretations in a scenographic key. See, for example, Herbert Croly, “New York’s Skyscrapers”, Architectural Record 61, no. 4, 1927, pp. 374-375; idem, “The Scenic Function of the Skyscraper”, ibid. 63, no. 1, 1928, pp. 77-78. But see Kenneth M. Murchison, “The Spires of Gotham”, Architectural Forum 52, no. 6, 1930, pp. 786, 878; see also the defense of free speculation by Paul Robertson,, president of the National Association of Building Owners and Managers, in “The Skyscraper Office Building”, ibid. pp. 879-880.

In McCormick's own words: “In 1904 or ‘05, Carter Harrison appointed a committee of aldermen to work in conjunction with a similar committee of the South Park Board to devise means of widening Michigan Avenue. Henry Foreman was chairman of this committee and I was secretary. At that time Mr. Lawson favored a plan for a tunnel from Randolph Street and Michigan Boulevard to some place on the north side (I believe preferably the present outer drive). Another plan suggested was double-decking Michigan Avenue originally to connect with Rush Street at Ohio. Our committee had two other members, Ernest Graham and Jarvis Hunt. Jarvis Hunt, in my presence, made the first suggestion of the present boulevard although he advocated a still wider boulevard than the one we have. Our committee recommended the improvement substantially as it has been built, but Mayor Dunne's board of local improvement was hostile. The project was later taken up by the Chicago Plan Commission”. See The International Competition for a New Administration Building for the Chicago Tribune MCMXXII (Chicago Tribune, Chicago, 1923) pp. 3-4n.

Ibid., p. 1. In this official publication of the competition, containing reproductions of the perspective drawings of all the entries, the newspaper’s contribution to the development of the city was carefully pointed out. According to the information it furnishes, the Chicago Tribune employed 13,000 people in 1922 and had a daily circulation of 4,000,000 copies.

Ibid., p. 3.

Ibid., p. 4. In 1921 the Michigan Avenue Bridge was built, breaking the barrier between the Loop and the area beyond the Chicago River; in 1919-21, Graham, Anderson, Probst and White built the Wrigley Building at 400 North Michigan Avenue.

The competition was opened on June 10, 1922, and the jury was composed of Alfred Granger of the American Institute of Architects, Joseph M. Patterson and Robert McCormick, directors of the Chicago Tribune, Edward S. Beck and Holmes Onderdonk, also of the Chicago Tribune. The jury was assisted by an advisory committee composed of B. M. Winston, chairman, Dorsey Crowe, E. I. Frankhauser, Sheldon Clark, Harvey A. Wheeler, and Joy Morton, who together represented the Chicago City Council, the Chicago Plan Commission, and the North Central Association. Thus the principal decision-making and consultative agencies of the city collaborated with the private initiative in the final verdict. On November 23, 1922, the jury was already able to indicate as prize-worthy a preliminary group of twelve designs, among which were those of Howells and Hood and Holabird and Roche. Saarinen's design arrived on November 29 and so impressed the jury that they decided to include it among the prize-worthy entries. On December 3, 1922, the final decision was announced: “Never before has the ‘quality of beauty’ been recognized as of commercial value by an American business corporation, and yet all the greatest architecture of the past has been based upon beauty as its fundamental essential…Let us hope that the results of The Tribune Competition may impress this essential upon the mind of American business so emphatically that the whole aspect of our American cities may be permanently influenced thereby. One gratifying result of this world competition has been to establish the superiority of American design” (International Competition, p. 44). See also the editorial published in the Chicago Tribune, on December 3, 1922. On the competition, see, in addition to the works cited in subsequent notes, Frank Schulze, “Chicago Architecture between the Two Wars”, in Oswald Grabe, Peter C. Pran, Frank Schulze, 100 Years of Architecture in Chicago (O’Hara, Chicago, 1976), pp. 41-43.

In 1922, the firm of William Holabird and Martin Roche included, in addition to the titular members, John A. Holabird, William’s son, John W. Root, Jr., and Edward A. Renwick.

In addition to the 145 designs presented by American entrants, foreign proposals were submitted as follows: Australia, 1 (that of Griffin); Austria, 5 (plus Loos’, which was sent from Paris); Belgium, 2; Canada, 4; Cuba, 2; Denmark, 2; England, 4; Finland, 2; France 6. Germany, 8; Holland, 11; Hungary, 4; Italy, 11; Luxembourg, 1; Mexico, 1; New Zealand, 1 (that of Lippincott and Billson); Norway, 3; Scotland, 3; Serbia, 1; Spain, 2; Switzerland, 6. There were 8 anonymous entries, among which that of the Luckhardt brothers. The absence of such figures as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Behrens – that is, of architects who were involved at the time with large-scale urban problems of theoretical dimensions exceeding the limits imposed by the competition – is significant. On Italian participation in the competition and the relationship of Italy to America in the matter of the skyscraper, see Giorgio Muratore, “Metamorphose d'un mythe: 1922-1943. Le gratte-ciel americain et ses reflets sur la culture architecturale italienne”, Archithese, no. 18, 1976, pp. 28-36.

Even outstanding firms of the Chicago school, such as Holabird and Roche or Schmidt, Garden and Martin, were careful not to stray from the reigning stylistic eclecticism; the mandatory qualitative distinction was sought in a montage of formal references drawn from the most varied European and non-European repertories. Within the general barrage of banality, a few of the designs submitted, including those by Bertram G. Goodhue or George F. Schreiber, or the design by Ralph Thomas Walker and McKenzie, Voorhees and Gamelin, Associated, stand out for their synthetic treatment of volumes while the proposal submitted by Frank Herding and W.W. Boyd, Jr., shows the influence of German Expressionist experiments on the faceted modelling of volumes.

See James Birrel, Walter Burley Griffin (University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, Brisbane, 1964), pp. 157ff.

Griffin’s design pursued a concept not unlike that of the entry by Albert J. Rousseau of Ann Arbor, Michigan, which won an honorable mention.

Condit, Chicago School, p. 209n46.

See Le Corbusier, Quand les cathédrales étaient blanches (Paris, 1937).

There exists no thorough critical analysis of Loos's design, but see Ludwig Münz, Adolf Loos (II Balcone, Milan, 1956); Ludwig Münz and Gustave Künstler, Das Architekt Adolf Loos (Schroll Verlag, Vienna-Munich, 1964); Mihaly Kubinsky, Adolf Loos (Henschelverlag, Berlin, 1970); Herman Czech and Wolfgang Mistelbauer, Das Looshaus (Löcker und Wögenstein Verlag, Vienna, 1976). On the relationship between Loos and American architecture, see Roland L. Schachel, “Adolf Loos, Amerika und die Antike”, Alte und Moderne Kunst 15, no. 113, 1970, pp. 6-1O; Leonard K. Eaton, American Architecture Comes of Age. European Reaction to H. H. Richardson and Louis Sullivan (MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1972), especially the chapter “Adolf Loos and the Viennese Image of America”, pp. 109-142. See also Massimo Cacciari, “Loos/Wein”, in Francesco Amendolagine and Massimo Cacciari, OIKOS. Da Loos a Wittgenstein (Officina, Rome, 1975).

Adolf Loos, “Die Chicago Tribune Column”, Zeitschrift des Österr. lngenieur- und Architekten- Vereines 15, no. 3-4, 1923, reprinted in Heinrich Kulka, Adolf Loos, das Werk des Architekten (Schroll Verlag, Vienna, 1931). I myself advanced' the hypothesis of an ironic intention in Loos’ column skyscraper in Manfredo Tafuri, Teorie e storia dell’architettura (1968; rev. ed., Laterza, Bari, 1976), p. 97.

Loos’ appreciation of Sullivan's work is witnessed by his intention of opening a school in Paris in the direction of which the old master would have a part. See Ester McCoy, “Letters from Louis Sullivan to R. M. Schindler”, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 20, no. 4, 1961, pp. 179-184.

I refer here to the distinction between art and architecture made by Loos in his 1910 lecture “Architektur”, published in Trotzdem and reprinted in Sämtliche Schriften Adolf Loos (Harold Verlag, Vienna-Munich, 1962), 1: 302ff.

Loos, “Chicago Tribune Column”.

Ibid.

According to Montgomery Schuyler, the first example of this type of tripartite skyscraper was George B. Post's Union Trust Building in New York (1889-90), a work of evident Richardsonian inspiration; see Schuyler, “Skyscraper Up-to-Date”. Weisman traces the origins of this type to an earlier work by Post, the Produce Exchange in New York (1881-84), which constituted a precedent for Richardson's own Marshall Field Warehouse, and to Post's Havermeyer Building in New York, in which the architect created a highly successful organism, also notable for its height. Particular note should be taken of the exceptional quality of Post's activity in general and of his role as inventor of structural models for the skyscraper. See Winston Weisman, “The Commercial Architecture of George B. Post”, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 31, no. 3, pp. 176-203.